Scripture, Language, and Authority in Christian Faith

Christians across traditions agree on one essential truth: the Bible is inspired, authoritative, and foundational to the Christian life. Where disagreement often arises is not whether Scripture matters, but how it is meant to be read and interpreted.

A common assumption—especially in modern Christianity—is that any sincere believer can arrive at correct doctrine simply by reading the Bible on their own. This assumption feels intuitive, spiritual, and even faithful. Yet it quietly overlooks a basic reality: written words do not interpret themselves.

To understand why this matters, we must begin not with theology, but with language.

A Simple Sentence, Multiple Meanings

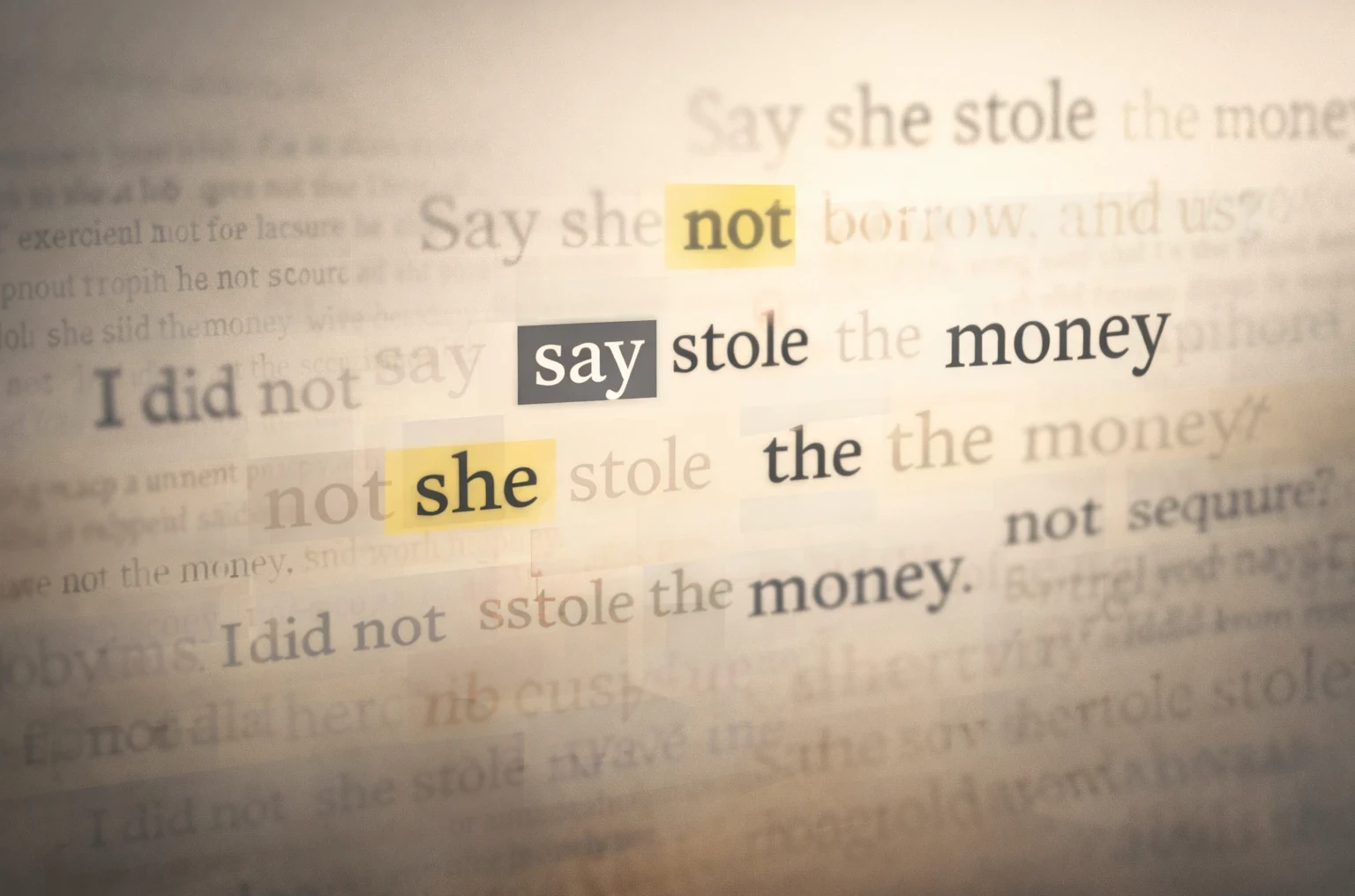

Consider the sentence:

“I did not say she stole the money.”

At first glance, it seems straightforward. Yet depending on which word is emphasized, the meaning changes entirely:

- I did not say she stole the money (someone else did)

- I did not say she stole the money (that accusation is false)

- I did not say she stole the money (I may have implied it)

- I did not say she stole the money (someone did, but not her)

- I did not say she stole the money (perhaps she borrowed it)

- I did not say she stole the money (something else was taken)

The words never change—yet the meaning does.

I have heard Catholic author and radio host Patrick Madrid use this sentence to illustrate how a written statement can carry different meanings depending on context and emphasis.

This example highlights a basic truth: meaning depends on context, emphasis, and shared understanding. If this is true of a simple modern English sentence, it becomes far more significant when reading ancient texts.

If Language Works This Way, Scripture Cannot Be an Exception

The Bible was written over many centuries, in ancient languages, across different cultures and literary genres. Meaning is shaped by history, audience, idiom, and context—none of which disappear simply because a text is inspired.

This raises an important question: if Scripture were entirely self-interpreting in the way modern individualism assumes, would interpretive disputes exist at all?

The Bible itself answers that question.

Interpretation Disputes Exist Inside the Bible Itself

One of the most overlooked facts in discussions about biblical interpretation is this:

The Bible records serious disagreements over what Scripture means—even among believers, apostles, and Church leaders.

If Scripture were self-interpreting in isolation, these disputes would be unnecessary. Yet they appear repeatedly.

Scripture Acknowledges Difficulty

2 Peter 3:15–16

“There are some things in them hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction.”

Peter admits that Scripture can be misunderstood—and that misinterpretation carries real consequences.

Competing Interpretations Among Christians

Acts 15:1–29 — The Council of Jerusalem

Some believers argued that circumcision was required for salvation. Others rejected this claim.

Resolution:

- Not by private Bible reading

- Not by “agreeing to disagree”

- Not by postponing truth with “we’ll see who’s right in heaven”

- But by apostolic authority meeting in council

“It has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us…” (Acts 15:28)

This is authoritative interpretation, not individual discernment.

Scripture Can Be Read—and Misread

Acts 8:30–31

“Do you understand what you are reading?”

“How can I, unless someone guides me?”

The Ethiopian eunuch is sincere, literate, and reading Scripture—yet he recognizes the need for guidance.

Scripture Warns Against Private Interpretation

2 Peter 1:20

“No prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation.”

This does not forbid reading Scripture; it forbids isolated interpretation detached from the apostolic community.

Paul Confronts Fragmentation

1 Corinthians 1:10

“That you be united in the same mind and the same judgment.”

Unity requires shared interpretation, shared teaching, and shared authority.

A Necessary Reconsideration

If interpretation disputes existed among the apostles, persisted in the early Church, and were resolved through authority rather than private judgment, then the modern assumption that Scripture alone—privately interpreted—is sufficient deserves serious reconsideration.

Written words do not interpret themselves. Scripture is no exception.

Why Language Itself Makes Private Interpretation Insufficient

Interpretation is not first a theological problem; it is a linguistic one. Meaning arises from context, usage, and shared understanding—not from words alone.

This is why contracts are litigated, laws are interpreted, and even simple instructions can be misunderstood. Scripture, written in ancient languages and distant cultures, requires even greater care.

Sincerity does not eliminate ambiguity. Prayer does not erase context. The question is not whether interpretation occurs, but who or what governs it.

Why Sincerity and the Holy Spirit Do Not Eliminate Interpretation

Jesus promised the Holy Spirit would guide His disciples into all truth (John 16:13). But that promise was spoken directly to the apostles in the Upper Room, whom Christ commissioned to teach and bear authoritative witness.

The Spirit fulfilled this promise uniquely by guiding the apostles in preserving Christ’s teaching and in the writing of Scripture itself.

For later believers, the Spirit’s role is illumination—not new revelation. He helps Christians understand and apply what has already been revealed. This guidance is formative and communal, not a guarantee of private doctrinal infallibility.

If sincerity alone ensured correct interpretation, Scripture’s repeated warnings against false teaching would be unnecessary.

Why “The Bible Clearly Says” Often Signals an Interpretation

“The Bible clearly says…” often means “this seems clear to me.”

Clarity is always clarity to someone. Different readers—equally sincere—reach opposing conclusions about baptism, salvation, the Eucharist, and authority. At that point, appealing to Scripture alone does not resolve the dispute, because both sides are already doing so.

Certainty Is Not the Same as Authority

Personal certainty does not equal doctrinal authority—even in Scripture.

Paul, despite receiving revelation from Christ, submitted his teaching to the apostles:

“I laid before them the gospel I preach… lest I should be running in vain.” (Galatians 2:2)

When the circumcision controversy arose, Paul and Barnabas did not resolve it privately. They brought it to the Church’s leaders (Acts 15).

Even apostolic certainty submitted to apostolic authority.

Why Doctrinal Unity Requires Authority

Unity is not optional in Christianity; it is commanded.

“One Lord, one faith, one baptism.” (Ephesians 4:5)

Without authority, interpretation fragments and unity dissolves. Authority does not compete with Scripture—it serves it.

Paul calls the Church:

“The pillar and bulwark of the truth.” (1 Timothy 3:15)

A pillar supports what it upholds; it does not replace it.

Scripture, Tradition, and the Community That Preserved the Text

The Church existed before the New Testament was complete. The faith was transmitted orally and communally before it was written.

“Hold fast to the traditions you were taught, whether by word or by letter.” (2 Thessalonians 2:15)

Tradition is not addition—it is transmission. Scripture emerged from the Church and was preserved by it. To sever Scripture from that community is to place upon individuals a burden Scripture itself never intended.

Conclusion: Reading Scripture Faithfully, Not in Isolation

The Bible is inspired, authoritative, and essential—but it was never meant to be interpreted in isolation from language, context, history, and authoritative guidance.

Scripture does not interpret itself. Sincerity does not eliminate ambiguity. Certainty does not create authority. From the beginning, Scripture was entrusted to a community that preserved, interpreted, and lived it.

Christian faith is not a private interpretive exercise. It is a received faith—handed on, safeguarded, and proclaimed within the Church.

Recommended Resources for Further Study

This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I may earn a commission at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Scripture

Acts 8; Acts 15; 2 Peter 1:20; 3:15–16; 1 Corinthians 1:10; 2 Thessalonians 2:15; 1 Timothy 3:15

Early Church Fathers

- Ignatius of Antioch, Letters

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies

- Tertullian, Prescription Against Heretics

- Augustine, On Christian Doctrine