For as long as Christians have debated doctrine, one question keeps coming back: where does ultimate authority in the Christian life come from? Is it Scripture alone, or is it Scripture alongside Tradition and the Church? The answer to this question shapes everything else—how we worship, how we interpret Scripture, and how we remain united in faith.

I grew up believing the Bible was the inspired Word of God, and I still do. The Catholic Church has always held that Scripture is “God-breathed” (2 Timothy 3:16) and without error. But over time I came to see that while the Bible is indispensable, it is not sufficient by itself. It was never meant to stand apart from the Church that received it, preserved it, and interprets it.

That’s why I cannot accept the doctrine of sola scriptura—the belief that the Bible alone is the final and sufficient authority for Christians. Instead, I believe Jesus intended a threefold foundation of authority: Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the living teaching office of the Church (the Magisterium). Like a tripod, each leg supports the others; take one away, and the whole structure wobbles.

In this article, I’ll explain the main reasons why I reject sola scriptura. These reasons are not only biblical but also historical and logical.

The Bible Does Not Teach Sola Scriptura

One of the first things that struck me is that the Bible never actually teaches sola scriptura. If this doctrine were true, it should be plainly stated somewhere in Scripture. Instead, what we find are passages that affirm the authority of Scripture but stop short of saying it is the only authority.

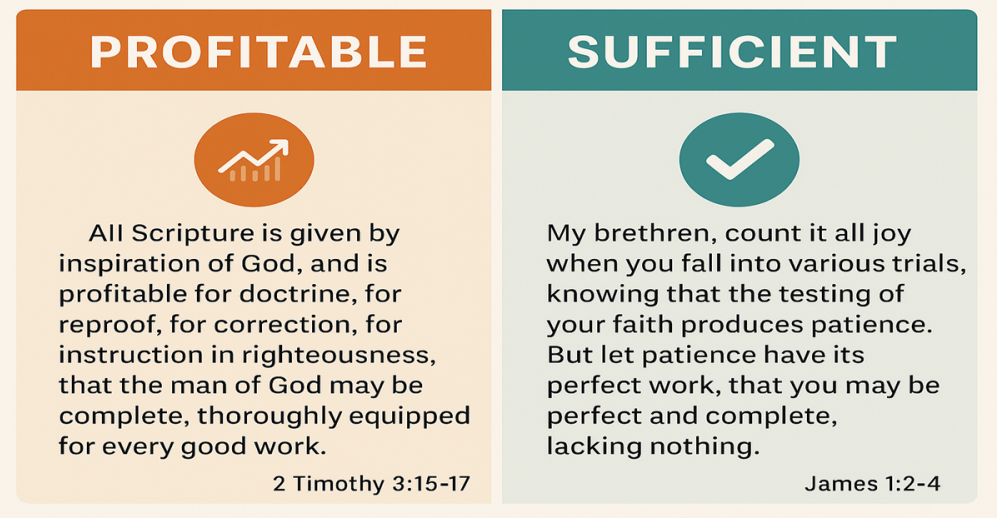

The classic text cited in support of sola scriptura is 2 Timothy 3:15–17, where Paul tells Timothy that Scripture is inspired by God and is “profitable for teaching, reproof, correction, and training in righteousness.” Protestants argue that this passage shows the Bible is sufficient for all Christian teaching.

But there are problems with this interpretation. First, at the time Paul wrote this, the New Testament was not yet complete. Timothy’s “sacred writings” referred to the Old Testament, not the Gospels or letters that had yet to be collected. If this passage proves sola scriptura, then technically it proves too much, because it would mean the Old Testament alone is sufficient.

Second, Paul says Scripture is “profitable” or “useful,” but he never says it is sufficient. Prayer is profitable. Faith is profitable. Good works are profitable. But we wouldn’t claim that prayer or works alone are the sole authority of the Christian life.

In fact, using the same logic, one could misinterpret James 1:2–4:

“My brethren, count it all joy when you fall into various trials, knowing that the testing of your faith produces patience. But let patience have its perfect work, that you may be perfect and complete, lacking nothing.”

If read in isolation, someone could conclude that patience alone is all-sufficient for Christian perfection. But no Christian would argue that patience by itself is the final authority of faith. This highlights the flaw of taking a single passage and stretching it beyond its intent.

Third, the same New Testament that praises Scripture also points to other sources of authority, such as the apostolic teaching handed down orally and the binding authority given to the Church (see Matthew 16:18–19; John 20:21–23; 1 Timothy 3:15).

In short, there is no verse that teaches the Bible alone is all that is needed for salvation and Christian life.

Scripture Affirms Apostolic Tradition

Another major problem for sola scriptura is that the Bible itself affirms the authority of Tradition. Paul explicitly tells the Thessalonians:

- “When you received the word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men but as what it really is, the word of God” (1 Thessalonians 2:13).

- “So then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter” (2 Thessalonians 2:15).

Notice that Paul makes no distinction between the authority of his spoken word and his written letters. Both are binding because both come from God. In fact, every book of the New Testament began as oral preaching before being written down.

For the first few centuries of Christianity, believers didn’t even have a complete New Testament. The canon was not finalized until the late 4th century. Until then, Christians relied on the authority of the Church to discern which writings were authentic. This means that the early Church did not operate on sola scriptura, but on a living Tradition guided by the Holy Spirit.

Fallible Interpretation Leads to Division

Suppose for a moment that the Bible were the only authority. That still leaves the question of interpretation. Who decides what the Bible means?

If every Christian is free to interpret Scripture for themselves, then it’s no surprise that Christianity has splintered into thousands of denominations, each with its own “biblical” view of baptism, communion, salvation, and countless other doctrines.

The result is a tragic irony: sola scriptura, which was intended to safeguard biblical truth, has instead led to endless contradictions. This is not what Christ prayed for when He asked that His followers be “one, as we are one” (John 17:21).

By contrast, the Catholic Church teaches that Christ established a visible authority—the apostles and their successors—to serve as the authentic interpreter of Scripture. The Magisterium does not replace Scripture but ensures it is understood faithfully. This protects the unity of the Church and preserves the truth of the Gospel.

Sola Scriptura Cannot Explain the Canon

Another issue is the canon of Scripture itself. How do we know which books belong in the New Testament? The Bible doesn’t give us a table of contents.

The canon was discerned by the Church through prayer, debate, and councils. The Synod of Rome (382), the Council of Hippo (393), and the Council of Carthage (397) all played roles in identifying the inspired books. Protestants and Catholics alike accept this canon, but only because the Church authoritatively declared it.

If the Church were fallible, how could we trust the canon to be infallible? As philosopher Peter Kreeft puts it, a fallible cause cannot produce an infallible effect. Without the Church, there would be no New Testament as we know it today.

The Bible Calls the Church the “Pillar of Truth”

Perhaps the clearest scriptural challenge to sola scriptura is found in 1 Timothy 3:15, where Paul calls the Church “the pillar and foundation of truth.” Notice that he does not give this title to Scripture, though Scripture is certainly true. Instead, he places that role on the Church itself.

The Church, despite having sinful members, is the Body of Christ and is guided by the Holy Spirit. Its authority in teaching faith and morals does not come from the holiness of its members but from Christ’s promise to preserve it from error.

Examples of Division: Baptism and the Eucharist

To see how this plays out in practice, consider two examples.

- Baptism: 1 Peter 3:21 plainly says, “Baptism… now saves you.” Yet Christians disagree sharply on whether baptism is necessary for salvation, symbolic only, or regenerative. If Scripture alone were enough, there would be no such disagreement.

- The Eucharist: In John 6, Jesus declares, “My flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink.” At the Last Supper He identifies bread and wine as His body and blood. The early Church universally believed in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. For the first thousand years of Christianity, this was not even disputed. Today, however, many Christians see communion only as symbolic.

These examples show that the question of authority is not academic—it has real consequences for how we live our faith.

The Witness of the Early Church

The writings of the early Church Fathers confirm that they did not believe in sola scriptura. Instead, they consistently upheld the authority of Scripture, Tradition, and the Church together. Heresies arose not because Scripture was lacking, but because individuals interpreted it apart from the Church.

As St. Augustine put it: “Heresies arise simply from this, that good Scriptures are ill understood, and what is ill understood in them is also rashly and presumptuously given forth.”

Conclusion: The Bible and the Church Together

I reject sola scriptura not because I think less of the Bible, but because I think more of it. An infallible book demands an infallible interpreter. Without one, the result is confusion and division.

The Catholic Church loves and reveres Scripture, venerating it “just as she venerates the body of the Lord” (Dei Verbum 21). Scripture is God’s Word, but it was entrusted to the Church so that it could be faithfully taught, preserved, and lived.

For that reason, I am not a “Scripture Alone” Christian. I am a Catholic, convinced that Christ gave us the fullness of authority: the Bible, Sacred Tradition, and the Church.

“Take heed to yourself and to your teaching; hold to that, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers.”

(1 Timothy 4:16)

*This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I may earn a commission at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Recommended Reading to Go Deeper: