A Quick Clarification: Catholics Are Christians

“Why be Catholic instead of Christian?” is a category mistake—like asking, “Why be fruit instead of apple?” Catholicism isn’t a rival to Christianity; it is Christianity in its fullness. Many denominations reflect parts of the biblical faith beautifully, but the Catholic claim is that Christ established one visible Church to guard the whole deposit of faith (cf. 1 Tim 3:15).

This article answers the sincere question behind that confusion: What, in practice, makes Catholicism different—and why does it matter? In a word: authority.

The Crux of the Difference: Authority That Teaches in Christ’s Name

“Authority” can feel like a dirty word. But biblically, authority is not domination; it’s service of the truth for the sake of unity and salvation. The Catholic claim is simple:

Jesus founded a visible Church and gave it the ability to teach definitively—to say “this is true, that is not”—in His name, by the power of the Holy Spirit, to the glory of the Father.

That’s not an appeal to some invisible, amorphous “body of believers.” It’s a claim about the concrete Church Jesus instituted and still leads.

Jesus Founded a Visible, Structured Church (Not an Invisible Idea)

In Matthew 16:18–19, Jesus says to Simon: “You are Peter (Rock), and on this rock I will build my Church… I will give you the keys of the kingdom… whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven.” This evokes Isaiah 22:15–25, where the Davidic king entrusts keys to a royal steward (a prime-minister figure) who exercises the king’s authority in his absence. Jesus, the Son of David, fulfills the kingship; Peter receives the steward’s keys.

From the start, the Church had leaders, succession, and structure—bishops, presbyters (priests), and deacons (Acts 1:20–26; 1 Tim 3). That structure wasn’t a later invention; it’s baked into the gospel’s logic: if Christ intends a kingdom, He wills a visible people with shepherds who can actually teach and govern.

How the Early Church Used That Authority: Acts 15

Acts 15 records a crisis: must Gentiles be circumcised to be saved? That question isn’t minor; it touches salvation and the continuity between the Old and New Covenants. Notice what the Church doesn’t do: it doesn’t say, “Everyone interpret the Bible privately.” Instead, the apostles and elders gather, debate, pray, and then pronounce: “It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us…” (Acts 15:28). The decision binds the faithful.

Two key observations:

- This wasn’t “Bible Alone.” The New Testament canon wasn’t even finalized yet.

- The Church taught definitively. Not advice, not a blog take—binding doctrine.

That pattern—councils, definitions, unity—is the Catholic pattern. It’s how the Church later condemned Docetism and Arianism and articulated what nearly all Christians affirm today: Jesus is true God and true man, and God is a Trinity of Persons (Nicaea 325; Constantinople 381).

Why “Bible Alone” Can’t Carry the Weight

Catholics love Scripture. But the Bible does not list its own table of contents. The canon is a Church judgment—discerned, guarded, and handed on by the same Spirit who inspired the texts. If you trust the Bible as infallible, you already rely on a Church act to know which books are the Bible.

It’s logically unstable to claim an infallible book without any authoritative interpreter. Without a living teaching office, sincere Christians fragment into competing readings. A Church that can say “this is what the text means” doesn’t diminish Scripture; it protects it and preserves unity (cf. John 17).

As G.K. Chesterton quipped in substance: I don’t need a church that only tells me when I’m right; I need one that can tell me when I’m wrong.

The Four Marks: One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic

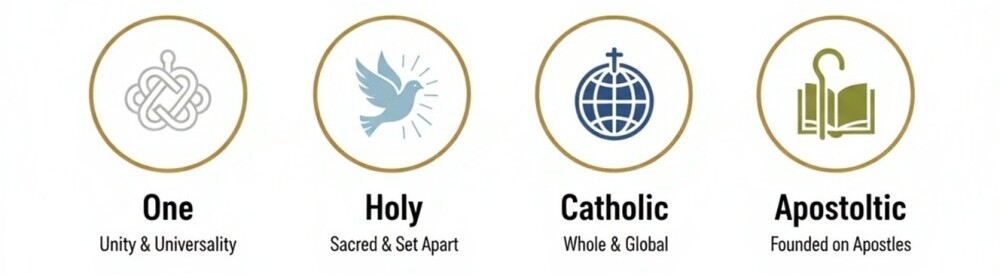

From the earliest creeds, the true Church is recognized by four notes:

- One – Visibly oriented to unity in faith, worship, and governance (John 17:21).

- Holy – Set apart by Christ’s presence and sacraments; calling sinners to sanctity.

- Catholic – According to the whole: universal in time and place, preserving all the truths without reduction.

- Apostolic – Built on the apostles, with successors (bishops) and a Petrine center (the Bishop of Rome) as a principle of unity.

Other communities can share aspects of these marks; the Catholic Church uniquely bears them in full.

Scripture, Tradition, and Magisterium—The Whole, Not a Slice

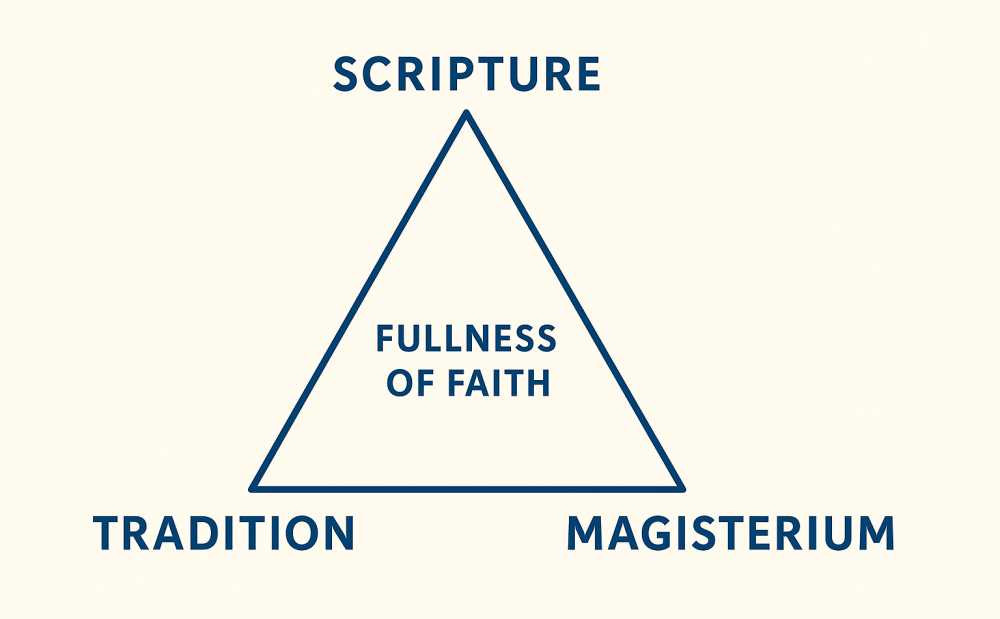

The Catholic “three-legged stool” holds together what the New Testament itself presupposes:

- Scripture – the inspired written Word of God.

- Tradition – the living transmission of apostolic teaching (2 Thess 2:15).

- Magisterium – the Church’s living teaching office that guards and authentically interprets both.

Cut off any leg and the stool wobbles. Keep all three, and the faith remains whole—not reduced to a slogan or a single emphasis.

Early Christian Witnesses: What Did the First Generations Say and Do?

Very early sources show a Church that looks recognizably Catholic:

- St. Ignatius of Antioch (A.D. 107) speaks of the Catholic Church and insists on unity with the bishop: “Where the bishop is, there is the Catholic Church.”

- The Didache (late 1st/early 2nd c.) presumes a hierarchical Church, speaks of baptism, and centers worship on the Eucharist.

- Fathers like Irenaeus and Cyprian witness to apostolic succession and Rome’s unique role as a principle of unity.

This isn’t a medieval add-on. It’s the continuation of the pattern we already see in Acts.

Why It Matters (More Than Ever)

In a world of sincere but conflicting interpretations, truth and unity are not luxuries. Christ didn’t found thousands of competing pulpits; He founded one Church that could preach, sanctify, and govern with His authority for every generation.

To “just be Christian” is good. To be Catholic is to belong to the Church Christ actually founded—the one that can still say, with the apostles, “It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us.”

The Catholic Church is also the visible “seed and beginning of the Kingdom”—already present in her sacramental and missionary life, moving toward its fulfillment at Christ’s return. In her, you receive not pieces of the Gospel, but its fullness.

Anticipating Common Questions

Isn’t Catholicism adding things not in the Bible?

No. The canon of the Bible itself is a Church discernment; Scripture points to a living Church with authority to bind and loose (Matt 16:19) and to forgive sins (John 20:22–23). Doctrines develop in clarity, but they do not contradict the deposit of faith.

Didn’t Jesus found an invisible church of all believers?

The New Testament shows a visible community with leaders who adjudicate disputes (Acts 15), ordain successors (Acts 1), and guard doctrine (1 Tim 3). Visibility and hierarchy are part of Christ’s plan for unity.

Why not “Bible Alone”?

Because Scripture doesn’t identify its own canon or promise private interpreters protection from error. Christ gave a Church—with Scripture, Tradition, and a living Magisterium—so that the Gospel would remain whole and the faithful united.

A Friendly Invitation

This isn’t about winning an argument; it’s about fidelity to what Jesus established. If you’re wrestling with the claims of Catholicism, read Matthew 16, Isaiah 22, and Acts 15 together. Ask the Lord where the Church is that can still teach with His authority. Then come and see.

“To be deep in history is to cease to be Protestant.” — St. John Henry Newman

References & Further Reading (starter list)

- Scripture: Matthew 16:18–19; Isaiah 22:15–25; Acts 15:1–29; John 20:22–23; 1 Timothy 3:1–7; 2 Thessalonians 2:15

- Early Church: Didache; St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Smyrnaeans; St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies; St. Cyprian, On the Unity of the Church

- Councils: Nicaea I (325), Constantinople I (381)

- Catechism: CCC 811–870 (Four Marks), 874–896 (Hierarchy), 888–892 (Magisterium)

Beautifully written, Emilio — this piece offers a clear, deeply grounded explanation of why Catholicism isn’t an alternative to Christianity but its fullness lived out in continuity with Christ’s design. I really appreciate how you trace authority from Scripture itself, connecting Matthew 16 and Isaiah 22 to the visible, structured Church Christ founded. The distinction between “authority as domination” and “authority as service of truth” is especially powerful—it reframes something many modern readers misunderstand. Your points about the canon of Scripture and Acts 15 highlight how the early Church functioned as a living, Spirit-guided body rather than a loose network of private interpretations. The historical witnesses you cite—Ignatius, Irenaeus, Cyprian—bring this to life beautifully. Overall, your reflection invites not debate, but deeper encounter with the Church’s unity, history, and sacramental life. A thoughtful and faith-filled read!

Thank you so much for taking the time to share this — I’m truly grateful for your thoughtful reading. I hoped to show that the Church’s authority isn’t something added on to Christianity, but the way Christ chose to preserve His revelation and keep His followers united in truth. Your comment captures that beautifully.

The more we look at Scripture and the earliest Christians, the more we see that the Church wasn’t a loose movement of individuals, but a visible family with real leaders, real accountability, and real continuity. That kind of authority isn’t about control — it’s about safeguarding what Jesus gave us so the Gospel isn’t remade according to personal opinion. I’m glad that came through in the article, and I appreciate your encouragement! God bless you on the journey. ✝️

Thank you for sharing this article on Catholic Christians. Catholics are Christians clears up for anyone who thought diffrently about the Catholic faith.

The beautiful images in this article are extremely impressing. They do help me be more interested in reading to learn more about each section.

The four marks is brand new information to me, I had no priior knowledge of Catholics before reading your article. Now I am curious to know more about them, one thing that comes to mind is if there bibles are the same as non-catholic faiths.

Jeff

Thank you so much for reading and for your kind words! I’m really glad the images helped make the topic easier to explore — the four marks are such a beautiful part of what Christians have believed from the earliest centuries, so it’s exciting to hear this was new and meaningful for you.

Regarding your question about the Bible: yes, Catholics and other Christians share the same New Testament — it’s identical in content. The difference is in the Old Testament. Catholic Bibles include seven additional books (such as Wisdom, Sirach, and 1–2 Maccabees) that were part of the early Christian Scriptures and widely used in the first centuries of the Church. These were accepted by early Christians long before any modern denominations existed.

I’m happy to share more if you’re curious — your questions are welcome! Thank you again for taking the time to read and engage.✨