A Catholic Response Inspired by Bishop Robert Barron

When “Prove God Exists” Misses the Point

In the early 2000s, a new wave of popular atheism swept across the West. Figures like Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens filled bookstores and television studios, insisting that religion was not only false but dangerous. Their challenge was blunt: “Prove God exists.”

Their style was sharp, confident, and often mocking. Yet, as Bishop Robert Barron has observed, their ideas weren’t new. They were old philosophical critiques—borrowed from 19th-century thinkers like Marx, Freud, and Feuerbach—dressed up for a new audience. What was new was the tone: dismissive, almost contemptuous, as though believers were naïve children clinging to fairy tales.

Ironically, their hostility did the Church a favor. It jolted many Catholics awake. For decades, Christian apologetics—the reasoned defense of faith—had been quietly neglected. But when the New Atheists went on the attack, they forced believers to rediscover the treasures of their own intellectual tradition. Thinkers like Augustine, Aquinas, and the Church Fathers had already wrestled with—and answered—many of the same objections centuries earlier.

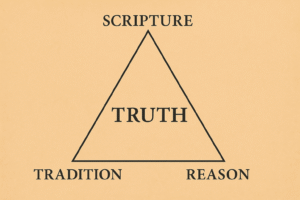

As Bishop Barron put it, “The New Atheists actually did us a service.” They reminded the world that faith and reason are not enemies, and that the Catholic tradition has always welcomed honest questions—because truth, wherever it is found, ultimately leads to God.

Faith and reason aren’t rivals—they complete each other. I explore this harmony further in The Bread of Life: Why Jesus Meant What He Said in John 6, showing how belief in Christ’s words is both profoundly spiritual and intellectually grounded.

The God Atheists Don’t Believe In

The heart of Bishop Barron’s critique is simple but profound: Most atheists reject a god that Catholics don’t believe in either.

When a skeptic demands proof of God, they often imagine God as a being within the universe—perhaps an invisible, powerful spirit floating somewhere “out there,” like Zeus with better manners. And then they look around and say, “I don’t see Him.”

But that’s not what the Church means by “God.”

God isn’t a creature within creation. He’s not one thing among others, competing for space in the cosmos. God is the reason there is a cosmos at all.

If you picture the universe as a giant painting, God isn’t the largest figure on the canvas—He’s the artist, the source of the painting’s very existence. The paint can’t explain the painter.

So when someone asks, “Where’s the evidence?” they’re treating God like a physical object that can be measured or detected—like a chemical element or a planet. That’s a category mistake. God isn’t part of the natural order; He’s the cause of the natural order.

As Bishop Barron says, the real question isn’t “Is there evidence of God?” but “Why does anything exist at all?”

The Question of Contingency

Philosophers call this the question of contingency—why finite, fragile, changeable things exist rather than nothing at all. Everything we see depends on something else for its being. You and I didn’t cause ourselves. The universe didn’t create itself. Even matter and energy don’t exist by necessity; they could have been otherwise—or not at all.

So where does existence come from? You can’t explain it by pointing to another contingent thing, because that thing also depends on something else. Sooner or later, you must reach a necessary being—something that doesn’t just have existence but is existence itself.

That is what God revealed to Moses in the burning bush:

“I AM WHO AM.” — Exodus 3:14

In other words, “My nature is to be.”

God doesn’t simply exist—He is existence. He is not a being among beings; He is Being itself.

Every creature receives its being as a gift, moment by moment, from the One who is Being in fullness. To borrow an image from the theologian Herbert McCabe, God is “singing the world into being” the way a singer sustains a note. If the singer stopped, the song would fall silent. Creation continues only because God keeps singing.

This reasoning echoes what St. Thomas Aquinas called the Five Ways—five rational demonstrations for God’s existence found in his Summa Theologica (First Part, Question 2, Article 3). Each begins with the observable world and leads the intellect to a single uncaused cause, the One whose very essence is to be.

I explore this question of God’s existence in more depth in Does God Exist? A Response to Common Atheist Objections, where I examine how reason, science, and revelation together form a consistent picture of the Creator behind all things

God Is Not “Up There”—He’s Right Here

So where is this God? Everywhere—and nowhere in the way we imagine.

Bishop Barron explained to Tucker Carlson that God is both transcendent and immanent. He is beyond creation, yet more intimate to it than anything else. You can’t point to God as if He were sitting in a chair in the room, but the room wouldn’t exist for even a second if He weren’t actively holding it in being.

St. Augustine captured it perfectly:

“God is higher than my highest and closer to me than I am to myself.”

That paradox—infinitely beyond us, yet closer than our own breath—is the mystery of divine presence. God is not another item in the universe, but the very condition for the universe’s existence. He is the light by which everything else can be seen.

When we truly grasp that, we stop thinking of faith as belief in an invisible object, and start seeing it as a relationship with the One who gives us existence itself.

Faith and Science: Two Different Questions

Tucker also asked Bishop Barron about Darwin and evolution. Barron’s answer was refreshingly balanced. Evolution, he said, is a question for scientists: How did life develop over time? Theology, on the other hand, asks a different question: Why is there life—or anything—at all?

Science studies what happens within the created world; theology asks about the source of the world’s existence. They are not competitors but partners in truth.

You can accept the evidence for evolution and still affirm creation, because creation doesn’t mean “a moment in time when things began.” It means the ongoing relationship between unconditioned Being (God) and conditioned being (creation).

“In Him all things were created, in heaven and on earth… and in Him all things hold together.” — Colossians 1:16–17

Whether you’re studying galaxies or genetics, you’re looking at how God’s creative word unfolds. As Barron often says, “God doesn’t explain the gaps in science; He explains the whole show.”

The Mystery That Reason Points To

Atheists often pride themselves on “following the evidence.” But evidence always presupposes existence. And existence itself can’t be weighed, measured, or photographed—it can only be received and wondered at.

When we ask for scientific proof of God, we’re like a character in a novel asking for evidence of the author’s handwriting inside the story. The author isn’t one of the characters; the author is the reason the story exists.

St. Thomas Aquinas put it simply:

“To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary.

To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”

Faith doesn’t cancel reason—it completes it. Reason can take us to the doorway of mystery; faith lets us step inside. To believe is not to stop thinking but to think more deeply—to recognize that every heartbeat, every breath, every sunrise is a word spoken by the One who simply is.

A Closing Reflection

When you ask, “Where is God?”, realize this: you couldn’t even ask that question if God weren’t already sustaining you in being. He’s not hiding in the stars or lurking behind the clouds. He’s the One holding you, and the stars, in existence right now.

We don’t “find” God the way we find an object—we awaken to the fact that we were never apart from Him. Every moment of our lives is a quiet miracle of participation in His being. As Scripture says,

“In Him we live and move and have our being.” — Acts 17:28

The New Atheists may have asked the wrong question—but perhaps, by doing so, they helped the rest of us ask the right one.

Related Reading: Does God Exist? A Response to Common Atheist Objections — exploring how reason and Catholic philosophy answer the question of God’s existence.

Further Reading:

• St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (First Part, Question 2, Article 3 – The Five Ways) – classic arguments for God’s existence based on motion, causation, contingency, degrees of perfection, and final cause.

This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I may earn a commission at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

To explore more of Bishop Barron’s reflections, visit Word on Fire Catholic Ministries

This post was inspired in part by a recent conversation between Bishop Robert Barron and Tucker Carlson.

To explore Bishop Barron’s videos and reflections, visit Word on Fire Catholic Ministries — one of the most thoughtful voices in Catholic evangelization today.

This is a thought-provoking read, and I appreciate you laying out this perspective so clearly. The central argument, that the question of God’s existence is not a purely scientific one but a metaphysical and personal one, is a crucial point of distinction in this ongoing conversation.

As someone who values dialogue between different worldviews, I’m curious about how you see this principle applying in reverse. For instance, from an atheist’s standpoint, might they feel that the question, “Why is there something rather than nothing?” is the right question, and that theistic answers can sometimes feel like they stop the inquiry prematurely? It seems the “right” question often depends on one’s foundational assumptions about what constitutes valid evidence.

Thank you for sharing a piece that encourages readers to reflect on the nature of the questions we ask, not just the answers we give.

Thank you for such a thoughtful question. You’re absolutely right that how we frame a question depends a lot on the assumptions we start with. From a Catholic perspective, we don’t see the question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” as a curiosity-stopper, but as a place where reason is meant to keep pressing deeper.

An atheist can feel that the theistic answer “God created the universe” ends the conversation too quickly. But in classical Christian thought, especially in Catholic philosophy, that answer is actually the start of a different kind of inquiry. If God is not merely a bigger being in the universe, but the very act of Being itself (as thinkers like Aquinas point out), then the question shifts from examining parts of reality to examining the deeper ground of all reality. We’re not explaining one physical thing with another physical thing—we’re asking what it means for anything to exist at all.

In that sense, “God” isn’t a plug for gaps we can’t explain scientifically; He is the reason why anything—including science, rational laws, and consciousness—can exist in the first place. Catholics believe that the human mind is meant to pursue both physical explanations and the metaphysical foundations behind them. Far from shutting down the search, theism broadens it.

So, while an atheist may see “God” as an endpoint to questioning, the Catholic view sees God as a horizon that calls for deeper reasoning, not less. In other words: faith doesn’t replace inquiry—it demands it.

Thanks again for raising such a meaningful point. Dialogue like this makes the search richer for everyone.✨

Your reflection offers a clear and compelling explanation of why many atheist critiques miss the deeper Catholic understanding of God. I appreciate how you show that the demand to “prove God exists” often treats God as a creature among creatures rather than the very ground of being. By highlighting Bishop Barron’s insights, you invite readers to move beyond superficial debates and toward the real philosophical question: why anything exists at all. The distinction between contingent creation and the One who sustains it is often forgotten, and your analogies help make that mystery accessible. I also value your emphasis on the harmony of faith and reason, which the Catholic tradition has long upheld. Posts like this encourage more honest, thoughtful dialogue and challenge both believers and skeptics to think more deeply. Overall, this is a thoughtful and enriching contribution for readers seeking depth and clarity.

Thank you very much for your thoughtful response. I truly like how you got to the substance of the piece. As you said, when people approach God as just another “thing” in the cosmos, the whole conversation gets off on the wrong foot. The Catholic tradition’s conception of God as the very root of being changes the question completely and allows for a far deeper conversation.

I’m glad you found the comparisons helpful and that you thought it was important to point out the unity between religion and reason. The Church has always protected that balance. It’s good to see that people are prepared to go beyond sound bites and genuinely think about the broader philosophical picture. Thanks again for adding to the discussion.

This is a really thought-provoking post! I appreciate how it reframes the question of God’s existence, highlighting that many atheists argue against a concept of God that Christians don’t actually hold. The distinction between God as a being within the universe and God as the ground of all existence is fascinating, and I love the analogy of God as the artist of the cosmos. How do you think this understanding of God as “Being itself” changes the way believers approach the relationship between faith and reason in everyday life?

Thanks so much for your question! Seeing God as Being itself really changes the picture. If God isn’t just another “thing” in the universe but the very Source of truth and existence, then faith and reason aren’t rivals—we need both. Our minds help us explore the world God created, and faith helps us go beyond what our minds alone can reach.

That’s why the Church doesn’t fear science or philosophy. If all truth comes from God, then wherever truth is found, we’re being led back to Him. Faith doesn’t replace thinking—it gives our thinking its deepest foundation.