In a world full of churches, denominations, and conflicting teachings, how do we know which one is actually following what Jesus and the Apostles taught? Is it even possible to tell? The answer is yes—but it starts by looking backward, not just around.

Many modern Christian groups claim they’re simply “going back to the Bible.” They reject the traditions of the early Church, calling them man-made or heretical. But here’s the problem: the Bible didn’t drop from the sky. It came through the early Church—the very people some say got it all wrong.

So let’s take a serious look at what the early Church believed and why it still matters today.

1. The Early Church Was Closest to the Apostles

It’s easy to forget: the first Christians didn’t have the New Testament. They had the Old Testament Scriptures, oral teaching, the Eucharist, and leadership from the Apostles and their successors.

These early believers spoke the same languages, lived in the same culture, and were taught directly by the Apostles or their disciples. They didn’t have to “guess” what Jesus meant—they were there or just one step removed from those who were.

If the Church immediately after the Apostles misunderstood the Gospel, then Christianity was never stable to begin with. But that contradicts what Jesus promised:

“I will build My Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” — Matthew 16:18

The idea that truth was lost for over 1,500 years and rediscovered by Reformers is not only historically shaky—it suggests Jesus failed to protect His Church.

2. The Early Church Gave Us the Bible

Think about it: you wouldn’t even have a Bible if not for the early Catholic bishops, councils, and communities who preserved, copied, and canonized the books of Scripture.

The New Testament canon wasn’t officially recognized until the late 4th century. For centuries, it was the Tradition and teaching authority of the Church that helped believers know what was and wasn’t authentic Scripture.

So to say, “We go by the Bible, not the early Church,” is to bite the hand that fed you the Bible in the first place.

You can’t separate the Scripture from the Church that gave it to you.

3. Apostolic Tradition Isn’t a Dirty Word

Many modern Christians are taught that “tradition” is bad—something Jesus condemned. But that’s not the whole story.

Jesus rejected man-made traditions that contradicted God’s word. But Paul commanded believers to hold fast to the Apostolic traditions:

“So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter.” — 2 Thessalonians 2:15

That’s both oral and written teaching—not just Scripture.

The early Church didn’t rely on personal interpretation. They followed the living Tradition passed on by the Apostles through the bishops—just as Jesus intended.

4. The Early Church Believed Things Modern Denominations Reject

Want to test if your church lines up with the early Church? Look at what the first Christians actually believed. Here’s just a sample from the early second century:

- Real Presence in the Eucharist

- Baptismal regeneration

- Confession to a priest

- Apostolic succession and bishops with real authority

- Prayers for the dead

- Veneration of Mary as the New Eve

- Unity around the bishop and Eucharist as the center of worship

These aren’t Catholic inventions—they’re ancient Christian teachings. Church Fathers like St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. AD 107), Justin Martyr (d. AD 165), and St. Irenaeus (d. AD 202) all affirm these beliefs, and they lived long before Constantine or medieval Catholicism.

So if your church teaches the opposite, who really changed the message?

5. Interpretation Without History Leads to Confusion

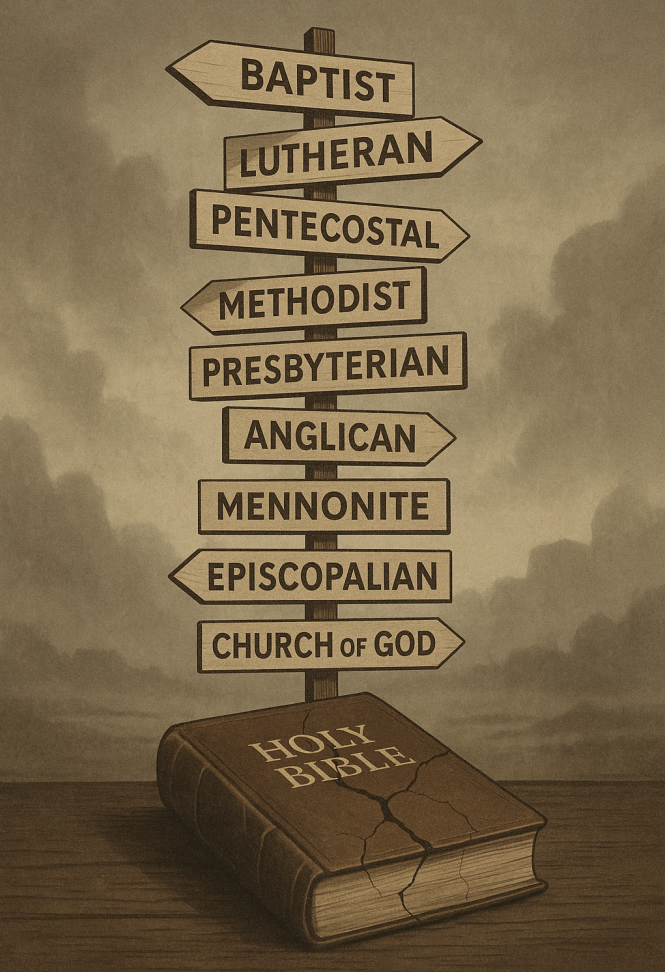

One of the slogans of the Reformation was Sola Scriptura—Scripture alone. But Scripture alone leads to division, not clarity.

There are now tens of thousands of Protestant denominations, all claiming to follow “just the Bible,” yet coming to wildly different conclusions on salvation, baptism, communion, authority, and more.

Why? Because without Tradition and authoritative interpretation, everyone becomes their own pope.

The early Church, by contrast, had a united faith. Yes, they debated things—but they resolved disputes through councils, bishops, and the Tradition passed down from the Apostles. That’s how we got the doctrine of the Trinity, the canon of Scripture, and the understanding of Christ’s nature.

Without that unity, Christianity becomes a free-for-all.

6. If the Early Church Was Wrong, Then the Gates of Hell Prevailed

If the Church immediately after the Apostles fell into heresy, what does that say about Jesus’ promise to protect it?

“He who hears you hears Me, and he who rejects you rejects Me.” — Luke 10:16

“I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” — Matthew 28:20

If Jesus entrusted His Gospel to the Apostles and their successors, then we can trust the Church they built. But if that Church got it wrong, then Christ’s words failed—or He left no way to reliably find truth.

That’s a bigger problem than people realize.

7. The Church Is a Visible Body, Not an Invisible Idea

Some say, “The true Church isn’t a visible organization—it’s just all believers everywhere who love Jesus.” But that’s not how the Bible describes it.

The early Church was structured—with bishops, priests, deacons, and sacraments. The Book of Acts shows them meeting, appointing leaders, correcting error, and maintaining unity. That pattern continued without break for centuries.

The Catholic Church, for all her flaws, is still standing—still teaching the same sacraments, the same Gospel, and the same Tradition. That’s not just survival. That’s divine preservation.

Final Thought: Truth Doesn’t Expire

Truth doesn’t evolve with culture. If the early Church held beliefs and practices that modern churches reject, that doesn’t mean the early Church got it wrong. It means we need to take a hard look at what we’re calling “biblical” today.

The Church Jesus founded is still here. It’s not perfect because people aren’t perfect. But it has preserved the deposit of faith, just as Paul commanded (1 Timothy 6:20), and just as Jesus promised it would.

The question isn’t whether the early Christians believed like us. The question is—do we believe like them?

Want to Go Deeper?

Check out the writings of these early Church Fathers:

- Ignatius of Antioch – Letters (c. AD 107)

- Justin Martyr – First Apology (c. AD 155)

- Irenaeus – Against Heresies (c. AD 180)

These aren’t Catholic propaganda—they’re ancient Christian voices. And they’re worth reading.

The point about the Bible not dropping from the sky is both hilarious and humbling it really puts things into perspective! It’s wild how many say they’re “just following the Bible,” while forgetting that the early Church gave us the Bible. Without those faithful early bishops and councils, we’d still be piecing scrolls together. That makes me want to give a spiritual high-five to St. Athanasius and crew

It also makes me wonder: How much richer would our faith be if we actually leaned into what the early Church taught, instead of trying to reinvent the wheel every generation? And how can we better help others see that Apostolic Tradition isn’t a dusty relic, but a living connection to Jesus?

Thank you for sharing that! I can relate to your experience—so many of us grew up thinking the Bible just existed, without ever questioning how it came to be or who preserved it. Once we realize that it was the early Church, guided by the Holy Spirit, that prayerfully discerned which writings truly reflected the Gospel handed down by the Apostles, it changes how we view both Scripture and the Church. And yes—spiritual high-five to St. Athanasius and all those early defenders of the faith!

You bring up a powerful question: how much richer would our faith be if we actually leaned into the early Church’s teachings rather than reinventing the wheel? The answer, I believe, is much richer. Apostolic Tradition isn’t dead history—it’s the lived faith of the first Christians, passed down and protected for our sake. It’s not a fallback; it’s our foundation.

Helping others see that starts with conversations just like this—humble, curious, and rooted in love for truth. When people begin to see that the early Church wasn’t just “figuring things out” but faithfully guarding what had already been received, they start to understand why Tradition matters. It’s not extra—it’s essential.

Thanks again for your thoughtful comment and for engaging so deeply with the post. You’re asking the right questions!

@Emilio Garza – very thought-provoking read — the emphasis on apostolic succession and sacramental life as defining traits of the true Church is both bold (and historically grounded). I appreciate, and respect, that your post doesn’t shy away from strong statements. “Truth Doesn’t Expire” and “Interpretation Without History Leads to Confusion” — these challenge readers to engage with faith not just spiritually, but structurally and historically.

The call to examine early Church foundations feels especially timely for me. A lot of solid practical aspects to life are being lost as people dismiss these foundations. But that is not necessarily new – as history shows. I wonder how different traditions in the church reconcile the tension between the ‘visible hierarchy’ and spiritual unity today – but for sure in my experience the idea that ‘everyone becomes their own pope’ is fatally flawed.

Thanks again.

MarkA

Thank you so much for your kind words and for taking the time to engage deeply with the article. I really appreciate your reflection — especially your insight that “truth doesn’t expire” and that dismissing historical foundations has led to confusion in our time. That’s spot-on.

You raise a great question about how different Christian traditions today reconcile the tension between the Church’s visible structure and the desire for spiritual unity. It’s a real challenge. Many communities have sought to preserve unity through shared beliefs or cultural ties, but without a visible, authoritative structure to anchor and safeguard doctrine, that unity often becomes fragile or superficial — especially when disagreements arise.

That’s why, from a Catholic perspective, the visible hierarchy (rooted in apostolic succession) isn’t in conflict with spiritual unity — it’s actually the means by which Christ preserves it. Jesus didn’t leave us with just a book or vague spiritual ideals — He established a Church with real authority: “He who hears you hears me” (Luke 10:16). That authority has always been exercised through visible leaders — bishops in communion with the successor of Peter — and it’s what has historically kept the Church unified in both doctrine and sacrament.

And I agree completely with your observation that the idea of “everyone becoming their own pope” is fatally flawed. When every individual becomes their own final authority on doctrine, the result is not unity but fragmentation — which is exactly what we’ve seen over the last 500 years. The early Church faced heresies not by appealing to individual interpretations but by gathering in councils, guided by the successors of the Apostles, to preserve the faith handed down.

Your comment shows a deep and thoughtful engagement with the history and structure of the Church, and I’m grateful for it. If you’re ever interested, I’d recommend exploring the writings of early Church Fathers like St. Ignatius of Antioch, who very clearly affirmed both spiritual and visible unity under the bishop and Eucharist-centered worship — a model that looks strikingly Catholic even in the first century.

Thanks again for sharing your thoughts!

Hello Emilio, this article really resonated with me! You did an amazing job breaking down why the early Church matters and how it connects to the faith we practice today.

I especially loved your point about how the early Church gave us the Bible—it’s something I hadn’t fully considered before, and it makes so much sense. The idea that rejecting Tradition means “biting the hand that fed us” was such a powerful way to put it.

Your comparison between modern denominational divisions and the early Church’s unity was eye-opening. It’s true—without a shared Tradition, interpretation becomes a free-for-all, and that’s something I’ve wrestled with myself. Reading this made me want to dive deeper into the writings of the Church Fathers to see how their teachings align (or don’t) with my own faith community.

One question I’d love to hear your thoughts on: How would you respond to someone who argues that later Church councils introduced errors or innovations? And do you think there’s a way for Protestants and Catholics to bridge this divide respectfully?

Thanks for such a thoughtful and well-researched piece. It’s refreshing to see someone tackle this topic with both clarity and charity. Keep writing—I’ll be looking for more from you!

Warmly,

Mitia

Thank you so much for your kind and thoughtful comment! I’m truly grateful it resonated with you.

I absolutely encourage you to dive deeper into the writings of the Church Fathers—especially the early ones often called the Apostolic Fathers, like St. Clement of Rome, St. Ignatius of Antioch, and St. Polycarp. What’s fascinating is that these men either knew the Apostles personally or were directly taught by their disciples. St. Irenaeus, for example, was a student of Polycarp—who himself was a student of the Apostle John. These early witnesses had “the Apostles’ words still ringing in their ears,” as one historian put it. They lived in the same cultural and linguistic world, surrounded by other living witnesses who could confirm or challenge what was being taught.

So when we compare the faith and practices of the early Church to our faith communities today, a helpful question is: Who was closer to the source? Who understood the idioms, the context, the oral traditions, and had firsthand access to those who walked with Jesus? The Apostolic Fathers offer a vital window into what the earliest Christians believed and how they worshipped.

As for your excellent question about Church councils and whether they introduced errors or innovations—this is where historical perspective is key. The very first Church council—the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15—provides the model. The issue at hand (whether Gentile converts had to follow the Mosaic Law) wasn’t explicitly answered in Scripture at the time. So what did the Apostles do? They gathered as a body of Church leaders, discussed and prayed, and then made a decision with the guidance of the Holy Spirit. They even sent out an official decree that began with the words, “It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us…” (Acts 15:28). That’s significant! This was the early Church in action—discerning God’s will through both Scripture and Spirit-led authority.

Later councils followed this same pattern. They didn’t invent new doctrines out of thin air—they clarified and defended what the Church had always believed when disputes or heresies arose. The Council of Nicaea (325 AD), for instance, didn’t invent the divinity of Christ—it formally defined what Christians had always believed in the face of the Arian heresy.

And I do believe Protestants and Catholics can bridge the divide respectfully. It begins with humility and a shared commitment to truth. When both sides agree to take history seriously, to listen rather than assume, and to recognize that Scripture emerged from a living Church—not the other way around—then fruitful dialogue becomes possible. And that’s a hopeful and exciting thing.

Thanks again for engaging so thoughtfully. Your openness and hunger to explore are exactly what the Church needs more of. Keep asking, seeking, and knocking!