1. The Foundations of the Eucharist: Historical and Biblical Context

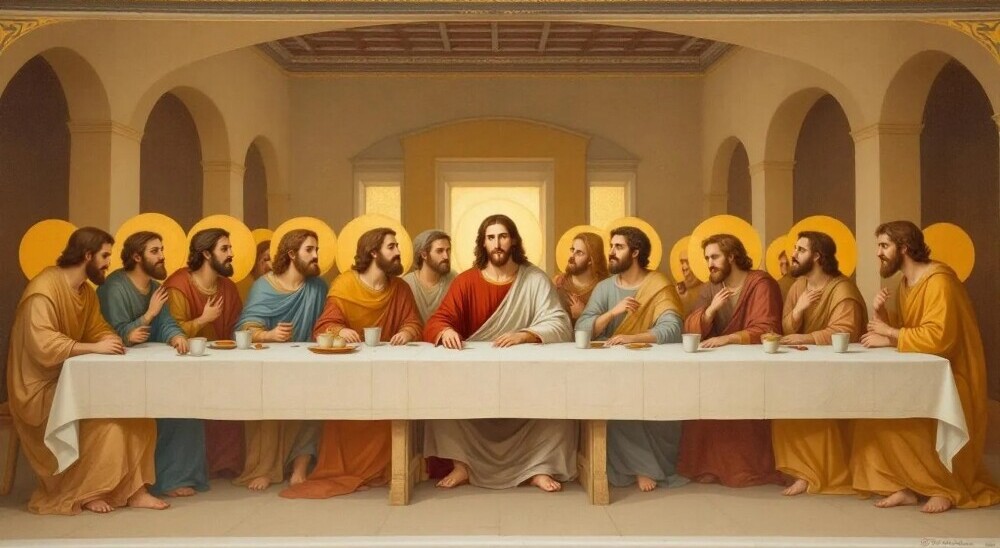

The Eucharist is not a late invention or poetic symbol—it is the living heart of Christianity, reaching back to the words and actions of Jesus Himself. At the Last Supper, on the night before His Passion, Jesus did something entirely new: He took bread, blessed it, broke it, and said, “This is my body, which will be given for you… This cup is the new covenant in my blood” (Luke 22:19–20). He wasn’t using metaphorical language. He was instituting a new covenant meal—a participation in His very sacrifice that would soon unfold on Calvary.

Scriptural Foundations: From Promise to Fulfillment

The Eucharist is the climax of salvation history. God has always fed His people with Himself. In Eden, humanity shared life with God. In the desert, Israel was fed with manna—bread from heaven that sustained them physically but pointed toward something far greater.

When Jesus declared,

“Your ancestors ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread that comes down from heaven, so that one may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats this bread will live forever—and the bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world.” (John 6:49–51)

He was drawing a direct line between the old covenant miracle and the new covenant reality. The manna prefigured the Eucharist—but now, instead of perishable bread, God gives His very self.

This was not allegory. The reaction of His listeners proves it—they argued, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” (John 6:52). Instead of correcting them, Jesus intensified His claim: “My flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink” (John 6:55). Many walked away, but He didn’t soften His words or retreat into symbolism. He meant exactly what He said.

After the Resurrection, this reality continues. On the road to Emmaus, the disciples recognized the risen Lord in the breaking of the bread (Luke 24:30–31). The same pattern—Word and Sacrament—became the enduring model of Christian worship, linking Scripture, covenant, and Eucharist as one continuous act of divine self-giving.

The Witness of the Early Church

The first Christians, taught directly by the Apostles, understood the Eucharist literally. St. Ignatius of Antioch (c. 107 A.D.), a disciple of John, wrote against those who “abstain from the Eucharist because they do not confess that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ.” For Ignatius, denial of the Real Presence was a mark of heresy, not Christian faith.

St. Justin Martyr (c. 155 A.D.) described how believers gathered on Sunday, offered bread and wine mixed with water, and after prayers, received not ordinary food, but “the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.”

Likewise, St. Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 180 A.D.), who was taught by St. Polycarp, a disciple of St. John the Apostle, affirmed:

“The bread which we receive is no longer ordinary bread, but the Eucharist, consisting of two realities, earthly and heavenly.” (Against Heresies, IV.18.5)

He argued that if the Eucharist is truly Christ’s Body and Blood, then it confirms the resurrection of our own bodies—because we are nourished by His real, life-giving flesh.

St. Clement of Rome (c. 96 A.D.), one of the earliest popes and a contemporary of the Apostles, referred reverently to the “offering” and “service” of the Eucharist in his Letter to the Corinthians, showing that the sacrificial character of the liturgy was already well established within decades of Christ’s death and resurrection.

St. Hippolytus of Rome (c. 215 A.D.), in his Apostolic Tradition, provided one of the earliest detailed descriptions of the Eucharistic prayer, emphasizing its sacredness and the belief that through consecration, the elements become sanctified by the Holy Spirit.

And St. Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 350 A.D.) later urged the faithful:

“Do not regard the bread and wine as simply that; for they are, according to the Master’s declaration, the Body and Blood of Christ. Even though sense suggests this to you, let faith make you firm.” (Catechetical Lectures, 22.6)

For these early saints and teachers—men who stood just one or two generations removed from the Apostles—the Eucharist was no metaphor. It was the same Jesus who died and rose again, made truly present under the appearance of bread and wine. The Church’s worship, unity, and identity were built around this conviction.

2. Transubstantiation: The Mystery of Transformation

At the heart of Catholic belief is transubstantiation—the change by which the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ while retaining their outward appearances. It’s not a poetic gesture or psychological reminder. It’s a metaphysical reality.

Theological Meaning: What Changes and What Remains

Catholic teaching distinguishes between substance (what something truly is) and accidents (its sensory properties). When the priest pronounces Christ’s words of consecration—“This is my Body… This is my Blood”—the substance of the elements changes entirely. What was bread and wine now is Jesus Christ, whole and entire: Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity. The accidents—taste, texture, color—remain so that we may receive Him without horror but in humility and faith.

This is no mere metaphor. The same God who created the universe from nothing can transform simple elements into His living presence. As the Catechism states: “The Eucharistic presence of Christ begins at the moment of the consecration and endures as long as the Eucharistic species subsist” (CCC 1377).

Historical Development

The belief long preceded the term transubstantiation. The Fathers of the Church—Ambrose, Cyril of Jerusalem, Augustine—spoke of a real change. The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) gave that mystery a name, and the Council of Trent (1545–1563) reaffirmed it against the Reformers’ symbolic reinterpretations, declaring that “by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance… which the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation.”

3. The Role of the Eucharist in Catholic Worship and Daily Life

The Source and Summit of Faith

Every Catholic Mass centers on the Eucharist. The Church calls it “the source and summit of the Christian life” (Lumen Gentium, 11). Through it, the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary is made present—not repeated—but mystically re-presented. The Mass unites heaven and earth, and through it, the faithful are drawn into the eternal offering of the Son to the Father.

Receiving the Eucharist is therefore not only a moment of personal devotion but of cosmic participation. The same sacrifice offered once on Calvary becomes accessible in every Mass across the world, every hour of every day.

Preparation and Reverence

Because the Eucharist is Christ Himself, preparation of heart is essential. Catholics examine their conscience, confess mortal sin, and fast before Communion. St. Paul’s warning still echoes: “Whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord unworthily… eats and drinks judgment on himself” (1 Corinthians 11:27–29). Reverence flows from faith—adoration before the tabernacle, silence in His presence, and thanksgiving after receiving Him.

Living the Eucharist

The Eucharist is not meant to end at the dismissal. It propels believers into the world, strengthened to live what they have received. It forms us into Christ’s likeness—teaching humility, patience, and love for others. To receive the Eucharist is to say yes to transformation, allowing grace to flow from the altar into our families, workplaces, and communities.

4. Modern Interpretations and Misunderstandings of the Eucharist

Misconceptions and Skepticism

Many today see the Eucharist as symbolic, an act of memory rather than mystery. But this view misses the depth of Christ’s words and the witness of His Church. If God can take on flesh in the Incarnation, He can make Himself present under the humble forms of bread and wine. The Eucharist is the continuation of the Incarnation—God dwelling among His people.

Interfaith Perspectives

Some Christian traditions view Communion as a memorial meal, others as a spiritual presence. Yet the Catholic understanding stands apart in its completeness: the Eucharist is both sacrifice and communion, the very Body and Blood of Christ. It is the means by which the Church participates in His eternal offering and receives divine life.

Renewing Eucharistic Faith

Surveys show that many Catholics no longer believe in the Real Presence. This is not merely a theological concern—it’s a crisis of relationship. Without the Eucharist, Christianity becomes sentiment rather than sacrament. The Church’s ongoing Eucharistic Revival seeks to restore understanding and awe, helping the faithful encounter Christ again in this sacred mystery.

Why It Matters

If the Eucharist were only symbolic, then Christianity would lose its center. But if it truly is Jesus—then everything changes. The Eucharist is proof that God not only came once in history but remains with us, body and soul, in every tabernacle. It is the bridge between Calvary and today, between heaven and earth.

When we kneel before the Blessed Sacrament, we kneel before the same Lord who was born in Bethlehem, died on the Cross, and rose from the tomb. His Real Presence is not sentiment—it’s salvation made tangible. The Eucharist is the pledge of our resurrection and the foretaste of heaven itself.

“Behold, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.” — Matthew 28:20

Related Articles Section:

Recommended further reading:

This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I may earn a commission at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

The Eucharist is a special part of the Catholic Mass where bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Jesus, a change called Transubstantiation. It reminds Catholics of Jesus’ love and sacrifice, and receiving it helps them grow closer to God. The Eucharist also gives strength to live with faith, kindness, and service in daily life. This is what I had always understood. This website had added onto by basic belief and reinforced some of what I have learned over the years. The information here has been presented in a manner that further explains not only historical context but also misinterpretations over time. I enjoyed reading through this and it helped me take a different look at the Eucharist and it’s significands!

Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts! I’m glad to hear the article helped deepen what you already believed and offered more context behind why the Church teaches what it does about the Eucharist. It’s beautiful how the more we learn about its history and meaning, the more clearly we see that it isn’t just a symbol of Jesus’ love—it’s His very gift of Himself, meant to strengthen and transform us.

I’m grateful you enjoyed the read, and I hope it continues to enrich your faith journey. If there are other topics you’d like to explore, feel free to share!

I found this post really thoughtful and thorough — it does a great job showing how the Eucharist is more than a symbolic ritual, linking its roots directly to the Jesus Christ’s Last Supper and the early Christian community’s understanding. The way the article traces historical testimony from early Church leaders and explains the doctrine of Transubstantiation makes it much clearer why the Eucharist remains central in Catholic worship. I especially appreciated how it connects the sacrament to both salvation history and everyday spiritual life. After reading this, I’m curious: how might this understanding change the way a believer approaches the Eucharist in daily life or community worship?

Thank you for your kind and thoughtful comment. I really appreciate how carefully you engaged with the article.

One of the most natural effects of this understanding is a change in posture—both interior and exterior. If the Eucharist is truly Christ and not merely a symbol, then approaching it becomes less about routine and more about encounter. Preparation begins to matter more. Silence, prayer, self-examination, and even small acts of fasting or recollection start to feel necessary rather than optional.

This also deepens reverence within community worship. The Mass is no longer something we attend as spectators, but something we enter into together—a participation in Christ’s self-giving. That shared belief quietly shapes how Catholics worship, how they treat sacred space, and how they understand unity within the Church.

Perhaps most importantly, this understanding doesn’t end at the altar. If we receive Christ sacramentally, it presses outward into daily life—calling us to live Eucharistically through charity, self-giving, and attentiveness to others. In that sense, the Eucharist becomes both the source and the pattern of Christian life.

Thank you again for reading so attentively and for asking such a meaningful question—those are often the ones that lead us deeper.